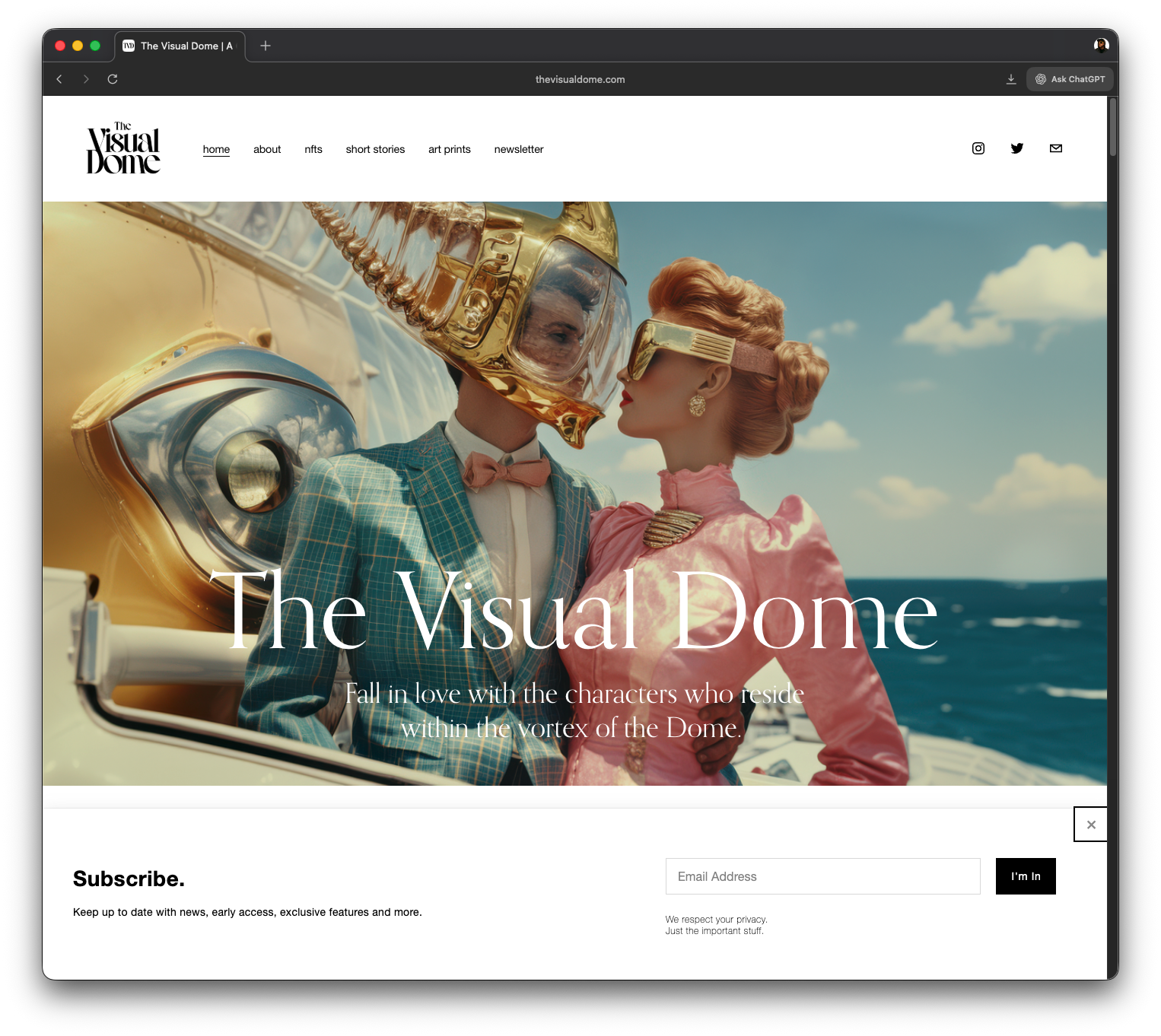

I don’t remember exactly when The Visual Dome showed up in my Instagram feed. It feels like one of those accounts that was just suddenly there, as an idea fully formed.

The images stopped me. Retro-futuristic figures. Masks. Helmets. Scenes that felt cinematic but slightly unreal, like stills from a movie that never existed. I liked the style immediately, but I didn’t really understand it.

And that bothered me a little.

I kept seeing this same look across AI images everywhere. Not just from this account, but across the platform. That soft retro surrealism. The sense of a future imagined decades ago. I wanted to know where it came from. Was it a preset? A prompt trick? A shared reference everyone was pulling from?

So I followed the account and kept watching.

The longer I looked, the harder it was to write it off as just a style. The images felt connected. Not visually identical, but related. Like they were all taken in the same place, even when the subjects changed.

I’d had that same feeling once before, with GossipGoblin. When I wrote about his project for The Daring Creatives, what stuck with me wasn’t the look of the work, but how it behaved. They felt like images from a real place, not a collection of isolated ideas.

That’s what I was noticing here with The Visual Dome.

Eventually, I did some research on Tony Rapacioli, the creator. Once I started reading interviews and paying attention to how he talked about the work, the images made more sense. Not because they were explained, but because of how he thought about them.

Tony didn’t come to this through AI culture. His background is in graphic design and photography, followed by years working in music technology and sound engineering (maybe someone I would describe as a Daring Creative?)

He’s described his mind as “a factory… firing 24 hours a day,” the same mental engine behind his music, art, and writing (from his own account on his site, tonyrapacioli.com/about-me-my-life).

That framing stuck with me. A lot of people generate constantly. Fewer people edit themselves.

In late 2022, Tony saw an image on Instagram that caught his attention because it didn’t seem feasible. The lighting. The scale. The implied production value. It looked like something that should have required a crew and a budget, not one person working alone.

A few weeks later, he found Midjourney.

The early experience wasn’t smooth. In a later interview, he said he spent “three days fighting with it” before anything worked the way he expected. Then, as he tells it, “11pm on one random night, tucked up in bed, it happened. I figured out how to prompt.” By the time he looked up, “it was 5am… my son was standing there asking why the heck I was still on my laptop” (recounted in Inside The Visual Dome, A World Prompted Into Existence With AI by Charlie Fink, Medium).

That’s where most explanations of AI art stop. Prompting. Keywords. Settings.

But the more I looked at The Visual Dome, the clearer it became that prompting wasn’t all there was to making visuals like these.

Continuity was.

To learn the backstory for The Visual Dome, make sure you visit the excellent website. So damned cool.

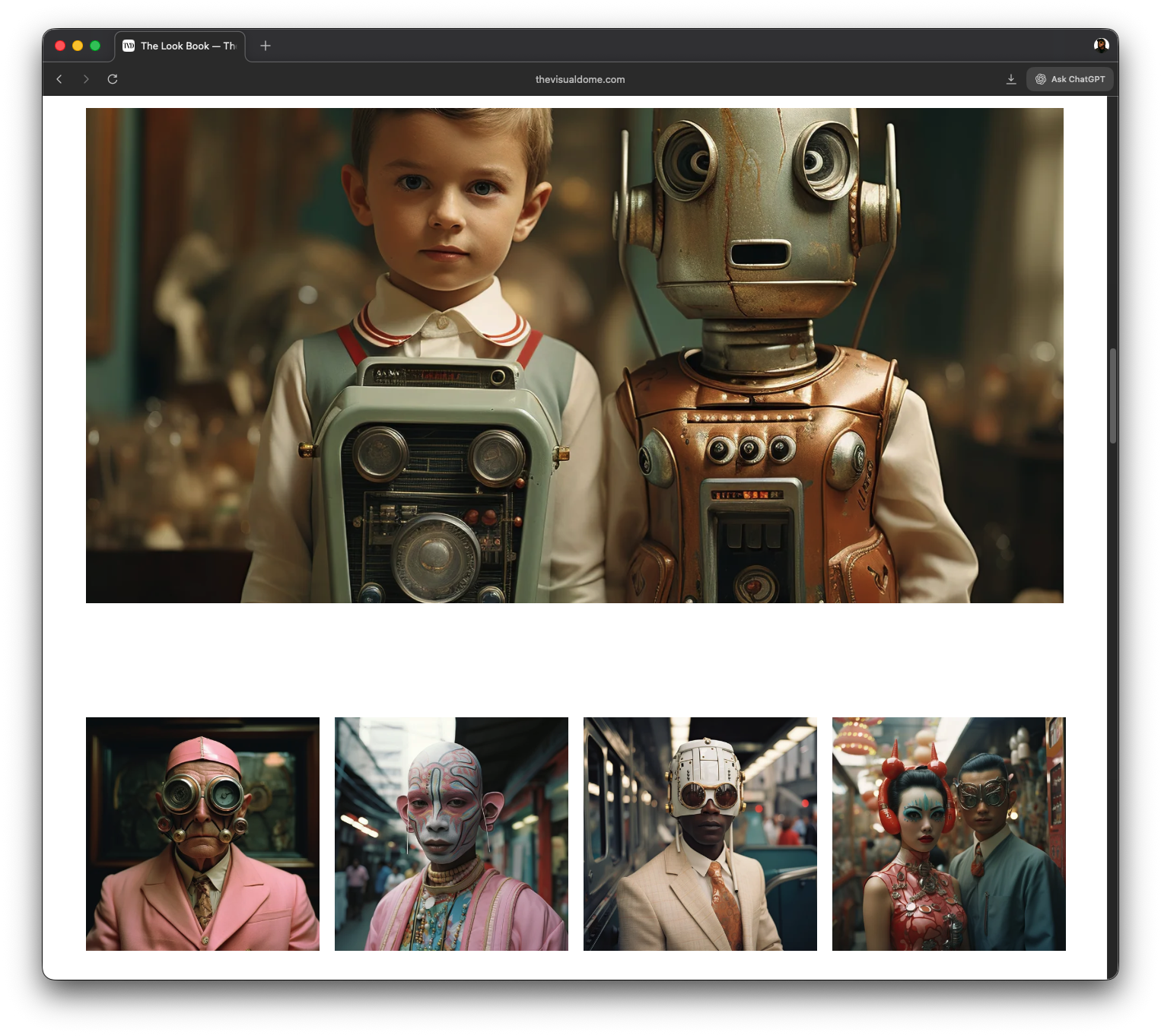

Tony has described his early process simply as “refining my style, keeping continuity,” even when that meant discarding images he liked. Images that didn’t fit the world didn’t survive, no matter how strong they were on their own (from the same Charlie Fink interview).

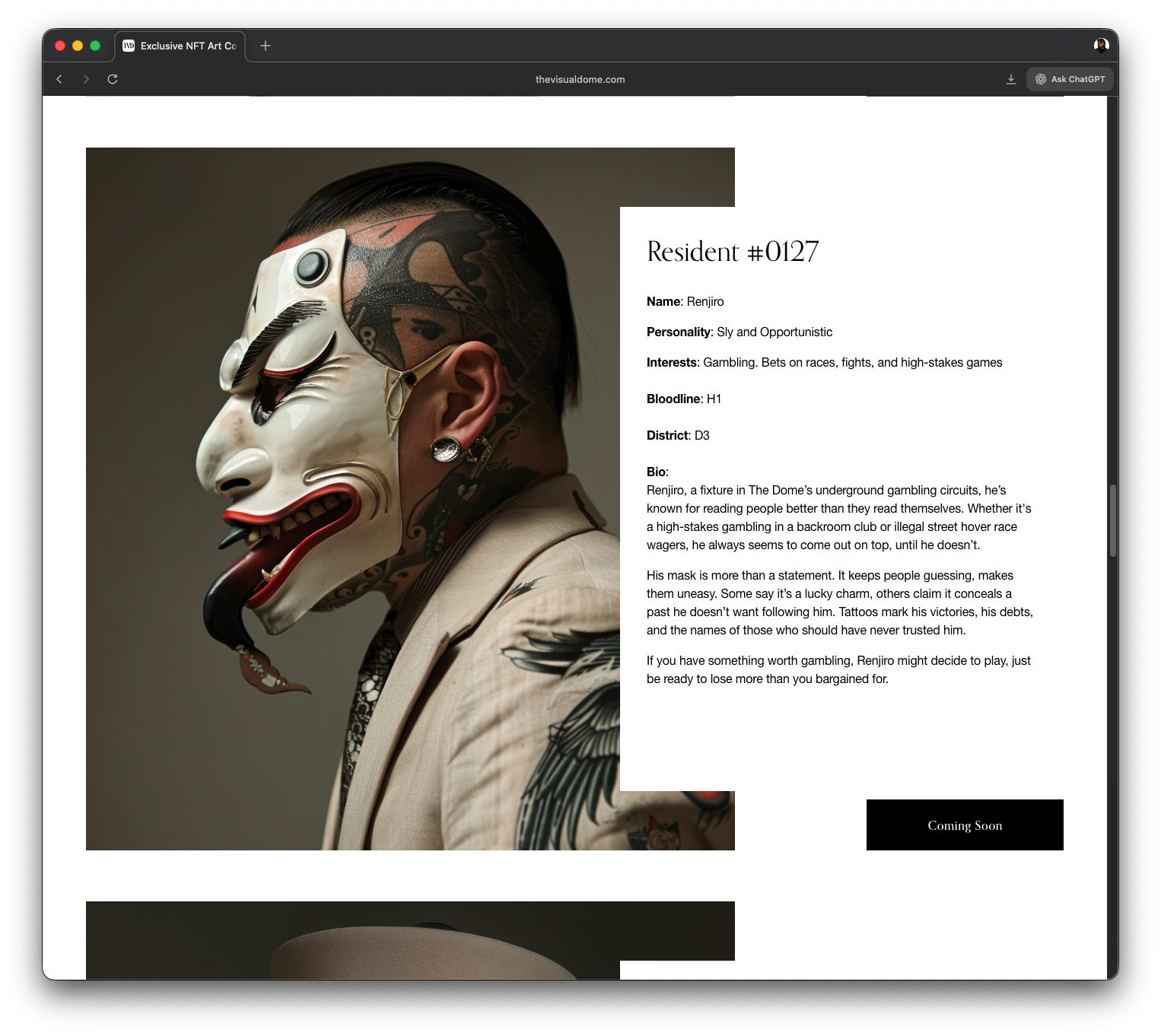

In the Visual Dome's world, colors repeat for a reason. Clothing signals social class. Certain technologies appear in some places and nowhere else. Masks aren’t decoration. They’re cultural.

The Visual Dome is divided into five districts, each with its own social structure and visual language. Tony has described it as a “parallel world where everything feels very familiar but is strangely different” (thevisualdome.com/history-of-the-dome).

Those distinctions aren’t explained every time. They don’t need to be. They’re embedded in the images themselves.

Early on, Tony realized something else too. The images weren’t enough on their own.

“They didn’t make sense,” he said. “They needed context.” That realization pushed him toward writing, even though he didn’t consider himself a writer before. AI, he later said, “sparked a love for writing, something I didn’t know I had” (from Sur Instagram, la recherche de sens des artistes utilisant l’IA, Le Monde, Feb 2024: https://www.lemonde.fr/pixels/article/2024/02/16/sur-instagram-la-recherche-de-sens-des-artistes-utilisant-l-ia-ces-images-ne-sont-pas-entierement-les-miennes_6216955_4408996.html).

The writing doesn’t explain the images. It gives them somewhere to live.

The workflow itself is surprisingly straightforward. Midjourney through Discord. Iteration. Upscaling. Light cleanup in Photoshop. The heavier lift is invisible: notes, rules, character details, and a growing internal bible that keeps the world from drifting.

Most people encounter The Visual Dome through Instagram, where images and short pieces of lore are released steadily. Over time, patterns emerge. Characters recur. Locations feel familiar.

Tony refers to the audience as “Domers,” and has said the world is becoming “as much theirs as mine” as people invest in its details and stories (reported in AI Art Project Captivates 700,000 Instagram Followers, CO/AI News, https://getcoai.com/news/ai-art-project-captivates-700000-instagram-followers/).

Prints, NFTs, and exhibitions came later, framed as extensions rather than pivots. Characters weren’t positioned as assets. They were positioned as residents. Ownership was treated as a way of being closer to the world, not extracting value from it.

The longer I’ve looked at The Visual Dome, the less I see it as mere AI art.

What’s interesting is the care. The editing. The decision to treat this like a place instead of a trick.

If you scroll fast, it’s easy to miss all of that.

But if you slow down, you can see how much is being held in place.

And once you notice that, it’s hard to look at the work the same way again.